The first two lines of the Crown’s opening statement in April at theĚýhigh-profile Hockey Canada sexual assault trialĚýclearly articulated what would become the dominant issue in a trial that captivated the country’s attention.

“This is a case about consent,” Crown attorney Heather Donkers said. “And, equally as important, this is a case about what is not consent.”

It’s an issue that will be finely parsed byĚýSuperior Court Justice Maria Carroccia when she delivers her verdicts Thursday in the case of five professional hockey players accused of sexually assaulting a young woman in a London, Ont. hotel room in 2018.ĚýWhether the judge finds the woman consented is yet to be decided; both sides have argued over what happened that night, and what it means with respect to Canadian law.

If nothing else, the case has shone a spotlight on consent, as experts believe it has driven home some key messages about what consent looks like, while also raising questions about the steps required to confirm a person’s consent.Ěý

“I think it goes to the broader importance of education on healthy sexual relationships,” said Kat Owens, interim legal director at LEAF, a prominent legal organization advocating for the equality of women.

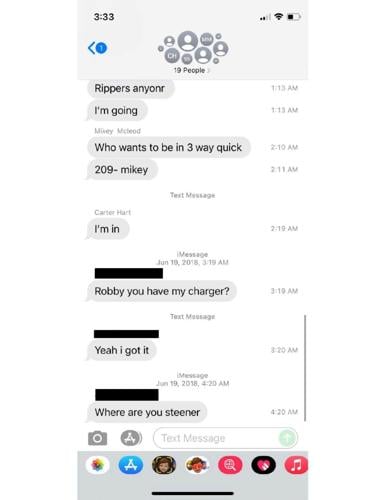

Michael McLeod, Alex Formenton, Carter Hart, Dillon DubĂ© and Cal Foote, all members of the 2018 Canadian world junior championship team, have pleaded not guilty to sexually assaulting the then-20-year-old woman in a room at the Delta Armouries hotel in the early hours of June 19, 2018. McLeod has also pleaded not guilty to being a party to a sexual assault for allegedly encouraging his teammates to engage in sexual activity with the complainant when he knew she wasn’t consenting.Ěý

Group text messages between some members of the 2018 world junior hockey championship team after they learned about an internal Hockey Canada investigation. (The texts appear in a multi-page court exhibit and have been excerpted by the Star to fit in a single image.)

The woman had met McLeod at Jack’s Bar earlier that evening while the world juniors were in London to attend the Hockey Canada Foundation’s annual Gala & Golf fundraising event and to receive their rings for winning the championship. Now widely known to the public as E.M., as her identity is covered by a standard publication ban, the woman returned to McLeod’s room where they had a consensual sexual encounter, only for multiple men to come in afterward, some prompted by texts from McLeod.

The Crown has alleged that McLeod had intercourse with the complainant a second time in the hotel room’s bathroom; that Formenton separately had intercourse with the complainant in the bathroom; that McLeod, Hart and DubĂ© obtained oral sex from the woman; that DubĂ© slapped her naked buttocks, and that Foote did the splits over her head and his genitals “grazed” her faceĚý— all without her consent.Ěý

While some of the accused players told police that E.M. was repeatedly demanding to have sex with men in the roomĚý— similar evidence was given by some of the Crown’s player witnesses at trialĚý— E.M. herself said during nine days of testimony that she only went through the motions as a way of protecting herself in a room full of men she didn’t know while she was drunk and naked. While she never said no nor resisted, she did not consent, she testified.

The Crown’s case for sexual assault “does not look the way it often does in the movies or on television,” prosecutors said in written closing arguments.

“The reality of what happened to E.M. is more nuanced. But it is equally a sexual assault, because she did not voluntarily agree to the sexual activity that took place in that room.”

Cal Foote does the splits at Jack's Bar in London on the night of June 18-19, 2018, while teammates Brett Howden (on the far side of Foote, in white with a lighter-coloured backwards ball cap) and Dillon Dubé (in white on the near side of Foote) clear space on the dance floor.

Ontario Superior Court exhibitThe law doesn’t recognize ‘implied consent’

Regardless of the findings made by the judge on the facts of this particular case, Owens said she believes the trial showed the public that theĚýidea of “implied consent”Ěý— that because a person didn’t say no or resist, they must have consentedĚý— isn’t recognized in law.

Consent needs to be “active, ongoing and communicated,” she said, voluntarily given by words or actions to each new sexual act at the time the person is engaging in it with each new sexual partner.

“I think that’s come through from the trial, which is valuable in terms of what we learn about consent,” she said. “We need to shift from that only ‘no means no’ framing to that ‘yes means yes’ framing.”

A person needs to be consenting in their mind at the time of the sexual activity, what’s known as subjective consent, said Lisa Dufraimont, a professor at York University’s Osgoode Hall law school. And they can’t give “broad advance consent,” meaning giving consent to future, undefined sexual activity, she said.

Nor can consent be given retroactively for past sexual activity, Dufraimont added — “There’s no such thing as post-event consent, period.” The trial spent some time on that point, given that McLeod recorded two videos of E.M. saying she was OK and that “it was all consensual.”

Michael McLeod films a selfie video with the complainant on the dance floor inside Jack's Bar.

Ontario Superior Court exhibitWas complainant’s apparent consent cancelled out?

The Crown has argued that E.M. either wasn’t consenting or her consent was “vitiated”Ěý— effectively cancelledĚý— by the fear of being in a room full of men she didn’t know. E.M. testified that her mind went on “autopilot” and she went along with everything in the room as a way to keep herself safe, later telling police and prosecutors that she adopted the “persona” of a “porn star” as a coping mechanism.

“The complainant’s fear need not be reasonable, nor must it be communicated to the accusedĚýin order for consent to be vitiated,” Donkers and co-counsel Meaghan Cunningham argued in written materials.

The defence teams have maintained that E.M. was consenting throughout the night. They pointed to testimony that E.M. was repeatedly demanding to have sex with the men, calling them “pussies” and becoming upset when many of them refused.

And they suggested that her “terror narrative,” that she was afraid to be in the room,Ěýwas cooked up in 2022 as part of her $3.5-million sexual assault lawsuit against Hockey Canada, which the organization quickly settled for an undisclosed sum.

When she first reported to London police in 2018, E.M. didn’t mention being scared, but rather maintained she was too drunk to consent.ĚýAs the Star first reported in May, police declined to lay charges,Ěýin part because of surveillance footage that raised doubts about her level of intoxication. (AtĚýtrial, the Crown didn’t argue that E.M. was too intoxicated to consent.)Ěý

It was only afterĚýnews broke of the Hockey Canada settlement thatĚýLondon police reopened their probe in 2022, underĚýintense public pressure.

What does having a ‘consent video’ mean, when it comes to a trial?

McLeod filmed two short videos of E.M. on his phone while in the hotel room that night, about an hour apart, with the second one being filmed shortly before she left. E.M. said she wasn’t even aware she was being filmed in the first clip, in which McLeod asks her off-camera if she’s “OK with this” and she responds: “I’m OK with this.”

The second clip shows a smiling E.M. wrapping herself in a towel and saying: “Are you recording me? OK, good, it was all consensual. You are so paranoid, holy. I enjoyed it. It was fine. It was all consensual. I am so sober, that’s why I can’t do this right now.”

E.M. conceded in her testimony that McLeod had been asking her at other times if she was fine, but that she just told him what she thought he wanted to hear.

The Crown pointed out that recording someone after the fact saying they consented is not evidence that they actually consented at the time of the sexual activity. But experts say there can still be value in such “consent videos” in a sexual assault trial.Ěý

A video could support an inference that a complainant was, in fact, consenting, depending on other evidence in the case and the circumstances surrounding the making of the video, said Lisa Kerr, a law professor at Queen’s University.

“It would be very strange to suggest that a video that purports to record an agreement may not serve as at least some evidence of that agreement, even if there may also be more to the story,” she said.Ěý

And a video could be used to make determinations about the complainant’s demeanour close in time to the alleged offence, Dufraimont said. “That would be a good example of a permissible use of that evidence.”

For instance, the defence has argued that E.M.‘s demeanour in the videosĚý— smiling, speaking coherentlyĚý— casts doubt on her claims she was intoxicated and terrified, which would affect her credibility as a witness.Ěý

“What he captured is critical evidence that she was happy and was fine with what was happening,” David Humphrey, McLeod’s lawyer, said in his closing arguments. “Time has proven that Mr. McLeod was right in his instinct to get some recorded confirmation of her consent and of how she appeared at the time.”

Consent videos can “cut both ways,” Owens with LEAF said.Ěý

“People might say it can be helpful to the defence if the person says they were intoxicated or upset, but they don’t appear intoxicated or upset,” she said. “But on the other hand, a person could ask: If you engage in consensual sexual activity, why do you feel the need to film after the fact?”

Hart offered up an answer to that question when he was being cross-examined by Cunningham during his testimony in May, an answer the Crown did not probe further: “Lots of professional athletes have done those things before.”

What if someone believes they have consent, but they are wrong?

Should the judge find that E.M. wasn’t consenting, an accused player could still be acquitted if Carroccia finds he had what’s called an honest but mistaken belief in communicated consent. For that defence to be available to an accused, the person must have taken reasonable steps to ascertain the complainant’s consent, something the Crown argues the players did not do.Ěý

Prosecutors argued the “reasonable steps requirement” was heightened in the “highly unusual circumstances” of this case, given that everyone involved could be assumed to have consumed alcohol, E.M. was a complete stranger, and was naked surrounded by clothed men she didn’t know in a small room.

Hart, for example, testified that he asked the complainant for “a blowie, meaning a blowjob,” that she said “yeah” or “sure,” and then moved toward him and helped pull down his pants before performing oral sex for about 30 seconds to a minute.

Even if the judge accepts that version of events, the Crown argues Hart needed to do more to confirm E.M.‘s consent. For example, taking her aside in the bathroom to ask her more questions privately, such as her name, what led up to this situation, whether this was something she truly wanted, or probe her desires.

Hart’s lawyer, Megan Savard, argued that the Crown was asking the judge to “extend the law beyond what the leading cases permit” regarding reasonable stepsĚý— “I’m not aware of any case saying you have to isolate a member of a group sexual encounter in order to get their consent.”

The entrance to room 209 is seen at the Delta Armouries hotel in London, Ontario on April 25, 2025.Ěý

DARRYL DYCK THE CANADIAN PRESSThere was also some evidence that, in response to the complainant’s repeated demands for sex, Formenton said he would do it, but not in front of everyone else; he then followed E.M. into the bathroom. Again, the Crown says this was insufficient.Ěý

“Had any of the men had a one-on-one conversation with her at the time of the impugned sexual activity, and she said she truly wanted the specific sexual activity with that man, it may not have meant she was actually consenting or enjoying it, but it would have meant that the accused had taken reasonable steps to ascertain her consent and thus had an available defence to the charge,” the Crown says in its written materials.Ěý

The Crown’s arguments raise the question as to just how many steps a person is supposed to take to ascertain consent; experts say there’s no exhaustive list of reasonable steps, nor a required number.

“It’s a really challenging issue, because it’s so context-specific,” Owens said. A couple in a long-term relationship may have developed specific ways of demonstrating their consent to sexual activity between them, she said, versus a woman in a room full of men she’s just met that night.

The law suggests that “more care and caution is required” in terms of reasonable steps in a situation where the parties are largely unknown to each other, or where the accused knows the complainant has been drinking alcohol, Kerr said.

“Having said that, if the trial judge accepts in this case that Carter Hart asked for oral sex and the complainant agreed, or that the complainant asked for sex and Alex Formenton agreed to do it provided they could do so privately, I would think that these are the kinds of words and actions that could suggest reasonable steps were taken,” Kerr said.

“Verbal discussion of willingness to engage in sexual activity is typically a stronger indication of reasonable steps than, say, relying on mere body language or physical actions.”

And a consent video may actually help to invoke this defence, Kerr said.Ěý

“It is obvious that discussing consent in a video or other recording may show that an accused was attempting to check on consent,” Kerr said.

“The key question in terms of the impact of the video will be whether it is sufficiently detailed and whether it appears to be a voluntary collaboration or, in contrast, if it appears to be something more like an attempt to cover up a wrong.”

If the Crown is found to be right on the question of reasonable steps, criminal defence lawyer Monte MacGregor wonders just how far a person needs to go.

“The thing about this caseĚýthat I find a little bit alarming is it appeared these accused men did everything you could do to obtain valid consent: they checked in multiple times, they listened to her, she made assertions, they videotaped a couple of comments,” said MacGregor, who is not involved in the case.

“What would be necessary if a standard like this leads to guilt? Does it mean you have to confirm with a written statement? That you have to videotape every interaction? Have a witness?

“It can’t get to the point where it necessitates such a rigid set of rules to obtain consent.”