No matter what had happened at school that dayŌĆöwhether great or ghastlyŌĆömy friends and I had only one thing on our minds as we headed for the neighbourhood variety storeŌĆöwhat chocolate bar to buy. There was so much choice, and so little allowance money. My choices were always gooey, chewy and melty. I agonized whether to spend my ten cents on Neilson Jersey Milk Treasures, MackintoshŌĆÖs Rolo or Rowntree Maple Buds. On Saturdays shopping with my mother and father, unlike me, both were quick pickers. My mother liked bars with crispy vanilla wafers and chose a Rowntree Coffee Crisp or Kit Kat, and my father, who liked his milk chocolate straight, chose either a Neilson Jersey Milk or Cadbury Dairy Milk.

Most of those bars are still best-sellers in Canada, and the history of the British and Canadian family firms who shaped the Canadian confections industry lies within their iconic branded wrappers.

John Cadbury, a Quaker, wanted to offer a nutritious, cheap and tasty alternative to gin which he saw ruining the lives of poor labouring families. After opening a tea shop in Birmingham, England in 1824, he began selling drinking chocolate and cocoa, which he initially made by hand, grinding cocoa beans with a mortar and pestle. By 1842 he was making 16 different kinds of chocolate drinks, and his first dark chocolate bar in 1849. Cadbury produced its first chocolate Easter Egg in 1875 and milk chocolate bar in 1897.

From the start, the goal of ŌĆ£Quaker capitalismŌĆØ as his descendant Deborah Cadbury terms it in ŌĆ£The Chocolate WarsŌĆØ was ŌĆ£for the benefit of the workers, local community, and society at large, as well as the entrepreneurs themselves.ŌĆØ The company established a pension fund, and provided free medical care. For his employees, in 1893, JohnŌĆÖs son, George built a model village, Bournville, with 370 homes on 550 acres, which included playing fields, a fishing lake, surrounding the Cadbury ŌĆ£factory in a gardenŌĆØ as it is described on CadburyŌĆÖs U.K. website.

Cadbury Dairy Milk, a milk chocolate bar with a higher proportion of milk than any previous bar recipe, and the first mass produced bar, was launched in 1905. It was the mainstay of the company and variations were developed ŌĆō Cadbury Flake in 1920, (crumbly ribbons of chocolate), Cadbury Dairy Milk Fruit and Nut in 1928, (with raisins and almonds) and Cadbury Crunchie in 1929, (honeycomb toffee coated in chocolate).

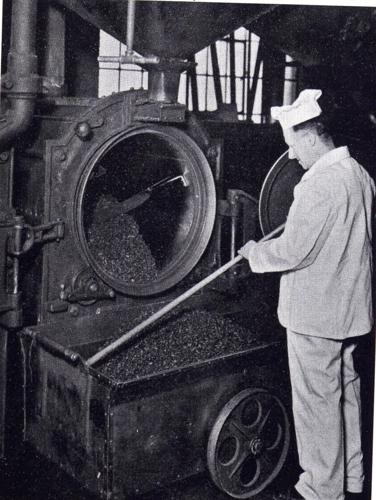

Cadbury’s mini-eggs are seen after being formed in a mold at the at the Cadbury Chocolate factory in ╬┌č╗┤½├Į on Friday Feb.18th,2005.

Tobin Grimshaw/The ╬┌č╗┤½├Į StarCadbury entered the Canadian market in 1919 when its British subsidiary, FryŌĆÖs, partnered with an American chocolatier to form The Canadian Cocoa and Chocolate company with a plant in Montreal. When the partnership ended in 1930, Cadbury modernized the plant, and began producing their flagship bar Dairy Milk there, among others.

Cadbury merged with Schweppes in 1996 and was subsequently taken over by Kraft Foods in 2010, whose confection division, Mondelez International, now runs it.

CadburyŌĆÖs fiercest rival in the chocolate industry was the Rowntree dynasty. Their rivalry (both planted worker spies in each otherŌĆÖs factories) inspired Roald DahlŌĆÖs classic childrenŌĆÖs novel ŌĆ£Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.ŌĆØ As a schoolboy, Dahl and his classmates at Repton boarding school tasted chocolate bars at CadburyŌĆÖs factory.

Henry Rowntree, also a Quaker, bought a cocoa production business in York in 1862, aiming as John Cadbury had, to provide cocoa and chocolate drinks as an appealing replacement for gin. The business struggled until his brother Joseph became his partner and French confectioner Claude Gaget joined the company. Gaget invented the original two products that financially consolidated the companyŌĆöin 1881 Fruit Pastilles (fruity, chewy candies), still sold under the Rowntree brand name and in 1882, Chocolate Dragees, sugar-coated chocolate beans, the first version of Smarties which was rebranded in 1937, and targeted at children (available in Canada since 1939).

Joseph Rowntree established a pension fund for Rowntree employees, as Deborah Cadbury details. He provided unemployment and sick benefits, free medical care and free education for employeesŌĆÖ children until age 17. A fervent advocate of affordable, decent housing, (his son Seebohm published a landmark social science study on city slums in 1901), he began building New Earswick, a garden village modelled on Bournville (in close consultation with George Cadbury) in 1902 on the outskirts of York for his employees and those living in YorkŌĆÖs slums. No pubs were allowed, as in Bournville. In 1904, he established several charitable trusts, funding the upkeep of village housing and social research, dedicating half of his wealth to them. It is still in operation as is CadburyŌĆÖs Bournville trust established in 1900.

Eager to enter the Canadian marketplace as a manufacturer rather than exporter of chocolates, in 1926 Rountree acquired the assets of Canadian chocolate company CowanŌĆÖs.

Rowntree continued to lag behind CadburyŌĆÖs, never coming up with a milk chocolate bar to rival Dairy Milk. In the thirties, Seebohm, now running the company, decided to turn the focus to the creation of new types of chocolate bars.

Aero, the aerated milk chocolate bar with the melty bubbly texture was launched in 1935, as was the Kit Kat bar with layers of crispy wafer coated in milk chocolate, available in Canada in 1937. Coffee Crisp, the Canadian adaptation of the Biscrisp bar (with coffee flavoured soft candy instead of chocolate between layers of vanilla wafer with milk chocolate coating) was invented in ╬┌č╗┤½├Į, and on the market in 1939. Rowntree was acquired by Nestle in 1988.

Aero, the aerated milk chocolate bar with the melty bubbly texture was launched in 1935.

robertson kateLike its British counterparts, the ╬┌č╗┤½├Į-based NeilsonŌĆÖs started as a small family business. After failing at several businesses, William Neilson decided to make ice cream to supplement his wife MaryŌĆÖs homemade mincemeat shop. He bought three hand-cranking ice freezers. Instead of using milk as most other ice cream makers were at the time, he used cream. The key to smooth and creamy ice cream lay not just in the cream content (21 to 24 per cent buttermilk) but to very rapid hand cranking; his second son Morden becoming the familyŌĆÖs official hand-cranker. He produced his first blocks of ice cream in 1893, which sold well enough for him to eventually construct a factory on Gladstone Avenue in 1906. Since ice cream was a seasonal business, to offer his workers year long employment, he got into the sideline of manufacturing bulk and boxed chocolates.

Following his fatherŌĆÖs death in 1915, Morden took over the business. He too aspired to create the milk chocolate bar equivalent of Cadbury Dairy Milk, and he did with Neilson Jersey Milk bar in 1924, which became CanadaŌĆÖs best-selling bar in the twenties. Another enduring Canadian barŌĆöNeilson Crispy Crunch was created by Harold Oswin. Oswin had joined the company at age 14 as a candy roller. He dreamed of inventing his own bar, kept experimenting, and his bar (hard peanut butter flake coated with molasses, sugar and vanilla dipped in milk chocolate) won a company contest and went on sale in 1930.

Morden was a hands-on manager, much admired by his employees. In his history of the company, David Carr writes that when Morden was diagnosed with leukemia, hundreds of his employees donated blood for the transfusions he required. As gravely ill as he was, Morden went to the homes of each donor to thank them personally. After his death in 1947, the company was bought by George Weston.

According to 2015 statistics from KPGM, Canadians eat 6.4. kilos or 160 chocolates bars a yearŌĆömany of the Canadian classic bars made at the original Neilson chocolate factory in ╬┌č╗┤½├Į on Gladstone, now owned by Mondelez International, and at NestleŌĆÖs Sterling Road plant in ╬┌č╗┤½├Į, the former site of CowanŌĆÖs since 1910, then Rowntree. The Gladstone factory produces half a billion chocolate bars a year, and the Nestle plant, 640 million.

Canadians have different taste in chocolates than Americans, preferring bars that are smooth and creamy in texture, sweet, with a higher fat content than American bars writes David Carr in his history of CanadaŌĆÖs confection industry. Those that are sold in the U.S., like Kit Kat, taste different, made to meet Americans preference for Hershey style bars. Hershey entered the Canadian marketplace in 1963, taking eighteen years to readjust the chocolateŌĆÖs formula. Canadians disliked its bitter taste, writes Carr, as did Swiss chocolatier, Hans Scheu, former President of Cocoa Merchants Association of America, who famously declared that Hershey had ŌĆ£completely ruined the American palette with his sour, gritty, chocolate.ŌĆØ

Hershey again retooled their Canadian formula in 2013. Cadbury, like Nestle, tweaks the recipe of bars sold internationally to meet each nationŌĆÖs taste buds,

For chocoholics, there is some the longing for the bars that got awayŌĆödiscontinued, despite pleas on Facebook, blogs, and even petitions. Old timers like Sweet Marie, (1931), made of caramel, fudge and peanuts; Malted Milk (tasting like a malted milkshake); Pep (dark chocolate with peppermint filling) as well as novelty bars appearing briefly on store shelves such as Neilson Choclairs in the mid 90s, an ├®clair like bar with chocolate filling, wafer and milk chocolate and Smarties Chocolate Bar in 2004, a solid chocolate with bits of Smarties.

I can still remember the sweet melty taste of Rowntree Maple Buds, one of CanadaŌĆÖs first chocolate treats, created by CowanŌĆÖs, one of their Maple Leaf branded chocolate line. I ate the chocolate buds slowly, one by one and nothing was sadder than the silence as I rattled the empty box.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation