Brett Howden wasn’t supposed to have so many memory problems.╠²

One of the Crown’s main witnesses at the Hockey Canada sexual assault trial, the Vegas Golden Knights centre╠²really couldnŌĆÖt recall much╠²about being in a room at the Delta Armouries hotel in the early hours of June 19, 2018, along with other members of the 2018 Canadian world junior championship team and a young woman Howden said was demanding to have sex with them.

Appearing virtually in a London, Ont., courtroom from the United States╠²wearing a hoodie╠²in May, he testified he couldnŌĆÖt remember whether the woman was upset; he couldnŌĆÖt remember if world juniors team captain Dillon Dub├® slapped her, or about sending a text to another player saying Dub├® smacked the womanŌĆÖs buttocks╠²so hard that it looked like it hurt; and he couldnŌĆÖt remember the woman getting dressed to leave but men persuading her to stay.

The prosecution said that HowdenŌĆÖs testimony had not proceeded ŌĆ£as anticipated,ŌĆØ and found itself in the position of having to argue that his memory loss was not ŌĆ£sincere,ŌĆØ but rather ŌĆ£feigned.ŌĆØ The Crown was calling its╠²own witness a liar.

It was just one example of the struggles faced by Crown attorneys Meaghan Cunningham and Heather Donkers to prove their case during the eight-week, high-profile sexual assault trial of five former world juniors who went on to play in the NHL,╠²which ended in acquittals╠²delivered Thursday╠²by Superior Court Justice Maria Carroccia. In doing so, the judge completely rejected the testimony of the complainant, known to the public as E.M. due to a publication ban on her identity, finding her evidence was both not credible and unreliable.╠²

ŌĆ£With respect to the charges before the court, having found that I cannot rely upon the evidence of E.M. and then considering the evidence in this trial as a whole, I conclude that the Crown cannot meet its onus on any of the counts before me,” Carroccia told a packed courtroom as dozens of people supporting the complainant rallied outside the building.╠²

The case that captured the country’s attention and sparked a reckoning about sexual misconduct in professional sports was always going to be a challenge to prove, not only because it’s notoriously difficult to secure a conviction in a sexual assault case, but because as the prosecutors themselves said during the trial, the case was more “nuanced” than what a person might think a sexual assault looks like.╠²

All five former players were found not guilty of all charges in the Hockey Canada trial, with the complainantŌĆÖs lawyer calling the judge's decision "devastating."

Kelsey Wilson/╬┌č╗┤½├Į StarE.M. never said no nor resisted, but testified she engaged in sexual activity with multiple players as a coping mechanism for being in a room full of men she didn’t know; she maintained that she was not consenting. But Carroccia found as a fact based on the evidence that E.M. did consent, that she was expressing her willingness to engage in sexual activity with the men throughout the night, and that contrary to the Crown’s arguments, there was no evidence that her consent had been “vitiated”╠²ŌĆö invalidated╠²ŌĆö by her fear of being in the room.╠²

To understand how the╠²players ended up being found not guilty╠²means taking a look at the few new pieces of evidence London police collected after reopening the case in 2022 against Michael McLeod,╠²Alex Formenton, Carter Hart,╠²Dillon Dub├®, and Cal Foote╠²ŌĆö a reopening the force itself acknowledged in court records was due to public pressure, and the fruits of which slowly began to unravel both before and during the trial.

It included a new written statement from E.M. outlining her allegations, one that she would later distance herself from in court as it contained errors that she blamed on her lawyers; a group chat from June 2018 that the Crown argued showed the players getting behind a false narrative about what happened in the hotel room,╠²but the judge thought otherwise; statements that the accused players were compelled to give to a Hockey Canada investigation that were then tossed from the criminal case because of the “unfair and prejudicial” way in which they were obtained; and then there was Howden and his memory problems, which meant that his text message about the Dub├® slap, that the Crown said provided╠²“very critical corroboration” for E.M.ŌĆÖs testimony, was excluded from the trial because he couldn’t even remember sending it.╠²

London police had originally investigated E.M.ŌĆÖs allegations in 2018,╠²but declined to lay charges after an eight-month investigation, as╠²the lead detective at the time doubted her claim that she was too intoxicated to consent based on her demeanour in surveillance footage. And he wondered in his report whether she had been an “active participant.”╠²

But everything changed in the spring of 2022 when TSN reported that Hockey Canada had╠²quickly╠²settled, for an undisclosed sum, E.M.ŌĆÖs $3.5-million sexual assault lawsuit brought against the organization and eight unnamed╠²John Doe╠²players. The public backlash was fierce, as sponsors began to dump Hockey Canada and the organization’s executives were called to testify╠²before Parliament.╠²London police was also feeling the heat.╠²

“Given a resurgence╠²in media attention, the London Police Service has reviewed this investigation with the aim of determining what other investigative means exist and whether reasonable grounds exist to charge any person,” London police officer David Younan wrote in 2022 in an application for a warrant to seize evidence.╠²

“The media attention surrounding this event is significant.”

Criminal defence lawyer Alison Craig, who is not involved in the case, wondered in an interview with the Star this month if the reopening was less about investigating whether a crime had been committed, and more about figuring out how to make criminal charges stick in the face of public outrage.╠²

“Because not a whole lot changed between investigation number one and number two,” Craig said. ”The police╠²should never be bowing to public pressure. It’s a really slippery slope.╠²If you start charging people as a result of public pressure, wrongful convictions and accused people’s lives getting ruined are going to skyrocket.”╠²

At a packed news conference last year announcing the charges,╠²London police chief Thai Truong apologized to E.M.╠²for the time it had taken to get to that point; on Thursday, the chief said little about his force’s investigation, other than noting in a statement that it had sparked important discussions about sexual violence.╠²

Crown attorneys have complete╠²discretion over which charges laid by police╠²ŌĆö if any╠²ŌĆö should be prosecuted. In Ontario, they’re required by policy to only prosecute if there’s a reasonable prospect of╠²conviction and it’s in the public interest, but they don’t have to publicly explain their reasoning.╠²

The test to prosecute is lower than in some other provinces ŌĆö such as British Columbia, where a “substantial likelihood of conviction” is required ŌĆö and one that critics have argued in the past needs to be changed to filter out weaker cases from Ontario’s backlogged justice system.

“The office of the Crown attorney knew what today’s verdict was likely to be, and the evidence at trial came as no surprise to them or anyone with full knowledge of the investigation,” Hart’s lawyer, Megan Savard, told reporters after Carroccia delivered her decision.╠²

As the Star first reported in May, Cunningham, the province’s lead sexual assault prosecutor as chair of the Crown office’s sexual violence advisory group, had even warned E.M. in a meeting several weeks before charges were laid in 2024 that it was╠²ŌĆ£not a really, really strong case,” but that a conviction was possible.╠²On Thursday, she told reporters that the success of a prosecution is “not measured solely by whether there are guilty verdicts at the end,” saying the Crown always wanted to ensure there was a fair trial.╠²

“Under the current╠²policy, there was next to no chance that this case wouldn’t proceed,” Michael Coristine, a former Crown attorney who now works as a criminal defence lawyer, told the Star this month.╠²

“It’s easy for defence lawyers╠²and people who aren’t in the Crown’s shoes to say ‘I would have pulled that case right away or never prosecuted it,’ but that’s not the reality that is being lived by these senior Crowns who do have these difficult decisions to make.”

‘No witness is a perfect witness’: E.M.ŌĆÖs testimony╠²

Crown attorney Meaghan Cunningham, and the complainant E.M., testifying by CCTV, are seen in a courtroom sketch in London in May.╠²

Alexandra Newbould The Canadian PressE.M. met McLeod at Jack’s Bar╠²with some of his teammates while the world juniors were in London for a fundraising event; she agreed to go back to his room╠²at the Delta Armouries╠²where they had consensual sex, only for multiple players to show up afterward, some prompted by texts from McLeod about a “3 way.”

Testifying in graphic detail╠²over nine days, E.M. said that the men placed a bedsheet on the floor and asked her to fondle herself, slapped and spat on her, obtained oral sex, and engaged in intercourse. She╠²testified that her mind went on “autopilot,” as she engaged in the sexual activity as a way of protecting herself while she was drunk and naked in a room full of strangers.╠²

The Crown alleged that McLeod had intercourse with E.M. a second time in the hotel room bathroom; that╠²Formenton separately had intercourse with her in the bathroom; that McLeod, Hart, and Dub├® obtained oral sex from her; that╠²Dub├® slapped her naked buttocks, and that Foote did the splits over her head and his genitals ŌĆ£grazedŌĆØ her face╠²ŌĆö all without her consent.╠²

During a marathon seven days of cross-examination by the defence, E.M. was confronted with the fact that the written statement she provided to police as part of their reopened investigation contained a number of errors. It╠²failed to mention that she initiated physical contact with McLeod on the dance floor at JackŌĆÖs, that she bought most of her own alcohol including a drink for McLeod, and kissed him. It also incorrectly stated she only learned later that he and his friends were hockey players, when she testified that she pieced together they were hockey players while at JackŌĆÖs.╠²

The statement had originally been written for a separate Hockey Canada probe, and in her testimony E.M. blamed her civil lawyers who drafted it for the mistakes.╠²“I was able to review the final copy, but really it wasnŌĆÖt something that I was taking the charge on I guess,” she testified.╠²

That did not sit well with the judge. “When confronted with inconsistencies between her evidence and her earlier statements, E.M. had a tendency to blame others,” Carroccia said.

London police chose not to re-interview E.M. as part of their reopened probe. Lead detective╠²Lyndsey Ryan testified that she believed the written statement╠²ŌĆ£did clarify some points,ŌĆØ and that a╠²new interview would have been “re-traumatizing.” Despite not interviewing her, Ryan felt that the statement suggested E.M. had come to realize between 2018 and 2022 that she╠²was not to blame for what happened in the room and that her “acquiescence did not equal consent,” according to part of Ryan’s report read in court.╠²

Michael McLeod films a selfie video with the complainant on the dance floor inside Jack's Bar.

Ontario Superior Court exhibitRyan acknowledged╠²on the stand it was “possible” she would have re-interviewed E.M. had there been no new statement. Court records suggest it played an important role in the decision to lay charges. Younan quoted parts of it in his application for a warrant, saying E.M. “most clearly expressed her subjective non-consent to any sexual activity” in the written statement.╠²

While police obtained surveillance footage in 2018 from Jack’s Bar, they never looked at it; investigators did analyze some of it in 2022, and the Crown argued it bolstered E.M.ŌĆÖs claim that she╠²was intoxicated because it showed how much alcohol she had consumed.╠²

But the defence used the footage to╠²their advantage,╠²pointing out that it showed E.M. buying most of her own drinks╠²when she had said the men bought most of the alcohol. And while she testified that the men were trying to move her hands toward their crotches on the dancefloor, McLeodŌĆÖs lawyer David Humphrey pointed out the only instance caught on camera was╠²E.M. appearing to touch McLeodŌĆÖs crotch without being directed.

The footage ended up causing the judge to find E.M. unreliable, and that she “exaggerated” her level of intoxication in her testimony.╠²As one example, E.M. testified she appeared in one clip to be drunk because she was leaning on the bar.╠²

“But a close examination of that portion of the recording seems to reveal that after ordering a shot for herself, E.M. looked at the change provided to her by the bartender, and she called her back because she had been short-changed,” Carroccia said, noting the bartender then returns to the cash register, removes a bill and gives it to E.M.╠²

“That conduct seems to be inconsistent with her assertion that she was leaning on the bar because she was drunk.”

Overall, the defence argued that E.M.ŌĆÖs “terror narrative” of being scared in the room was something she and her lawyers cooked up in 2022 for her lawsuit, as she never told police in 2018 that she had been scared.╠²╠²

“They were all like ‘no you f—- her, no you f—- her’...I don’t know what they were getting at with that...I think I was just getting frustrated at that point,╠²I’m like ‘seriously guys,’” E.M. told Det. Steve Newton during the first police investigation in 2018.╠²

“I would get annoyed when like, when things weren’t happening.”╠²

She told Newton that╠²at first,╠²“I was liking the attention for a little bit,” but that as the night went on and the alcohol wore off, “I was realizing what’s happening, I was sobering up, like I would get up to the bathroom, I would start crying.”

In court, she testified she was “worried” when men made comments about “putting golf balls in me, in my vagina, and asking if I could take the whole club...It just sounded really kind of extreme and painful.” But in 2018 to London police, she referred to the men’s golf ball comments as them “joking” and “just being stupid” and making fun of her.╠²

Carroccia pointed to E.M.ŌĆÖs words to the police in 2018 in her findings that there wasn’t evidence to support the argument that E.M. was scared to be in the hotel room.╠²

╠²

Unlike defence lawyers, who╠²typically meet a number of times with their clients, Crown attorneys have limited interactions with their witnesses prior to trial, and so may not always be aware of problems with their version of events until they come out in cross-examination, Coristine said.╠²

“No witness is a perfect witness,” he said.╠²

Crown preparation meetings are typically limited to explaining to people what to expect once they take the stand. Coristine explained that any clarifications or entirely new details offered in those╠²meetings by complainants would then have to be disclosed to the defence, who can use that information in cross-examination.╠²

“The Crown has to rely on what the victim has already told the police,” he said.╠²“The Crown isnŌĆÖt typically looking to get new information.”

‘This witness is generally useless’

The Crown described╠²Howden in their closing arguments as a “complicated witness.” One of only two players called by the prosecution who were in the room when some of the sexual activity happened, Howden either couldn’t remember certain things he had told the police and Hockey Canada’s investigation, or he gave answers on the stand that were inconsistent with what he had said in those other statements.

Where he was helpful for the╠²Crown was putting names to allegations, as E.M. couldn’t identify most of the men in the room; Howden testified╠²seeing Hart and McLeod receive oral sex from the woman at different times in the night, after she repeatedly demanded to have sex with players. He also remembered the woman ŌĆ£takingŌĆØ Formenton to the bathroom.╠²

Howden’s testimony prompted Cunningham to ask for Carroccia’s permission to cross-examine her own witness about his inconsistencies, but first she would need to convince the judge that Howden’s memory loss was not genuine.╠²

“It’s the Crown’s submission that Mr. Howden’s memory loss is a feigned memory loss, not a sincere one,” Cunningham said in May.╠²“His memory loss, in my submission, is directly related to details╠²that will be particularly damning for the defendants who are his former teammates and friends.”╠²

Howden “seemingly had a very clear memory” of the complainant “begging guys to do stuff, being flirtatious, being the one instigating everything,” Cunningham said, yet failed to remember he had previously reported the complainant weeping in the room, and men persuading her to stay when she would start to get dressed to leave.╠²

“The very fact that the details he claims not to remember are the details the Crown is most interested in ŌĆö and that they are the details that his friends and former teammates would not wish to have before the court╠²ŌĆö that is enough for Your Honour to say there is evidence that this is not a sincere memory loss,” Cunningham said.╠²

Savard argued that it╠²was a “pretty tall order” for the Crown to suggest that their own witness had come to court to “perjure himself╠²for, as far as I can tell, a group of men he hasnŌĆÖt really talked to in seven years.”╠²She argued that Howden was a witness who had trouble expressing himself.

“The witness is plainly unsophisticated, he didnŌĆÖt come to court dressed for court,” Savard said, referring to Howden’s hoodie, which never made another appearance during his time on the stand.╠²“He is inarticulate,╠²a poor communicator, and careless with words...If╠²anything, we may all say at the end of the day this witness is generally useless, but heŌĆÖs certainly not helpful to the defence.”╠²

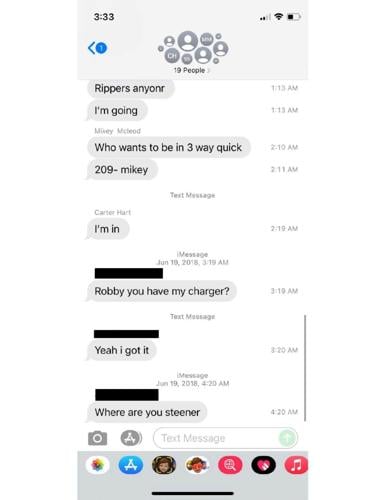

Group text messages between some members of the 2018 world junior hockey championship team after they learned about an internal Hockey Canada investigation. (The texts appear in a multi-page court exhibit and have been excerpted by the Star to fit in a single image.)╠²

Ontario Superior Court ExhibitCarroccia concluded that Howden’s memory loss was not feigned, and the Crown abandoned its application to cross-examine him.╠²

E.M. repeatedly demanding to have sex was a central feature of both Howden’s and player Tyler Steenbergen’s testimony for the Crown; prosecutors asked the judge to reject that part of their own witnesses’ evidence, arguing it was a false version of events cooked up by members of the team through a group chat in June 2018. But Carroccia found that the group chat simply showed the players “expressing their honest recollections” of what happened in the room, after finding out that Hockey Canada was looking into the alleged incident.╠²

ŌĆ£On the basis of all of the evidence, I find as fact that the complainant did express that she wanted to engage in sexual activity with the men by saying things like ŌĆśIs someone going to fŌĆö- me?ŌĆÖ and masturbating,ŌĆØ Carroccia said.╠²

It’s not unusual for either side to ask that parts of their witness’s testimony be accepted or rejected, Coristine said. “But the more material you’re asking a judge to parse out╠²ŌĆö asking them to accept this, but don’t accept that ŌĆö you run the risk of watering down the case,” he said.╠²

Text message ‘important to the Crown’s case’ is excluded

The Crown fought hard to have admitted as evidence a text message Howden sent to fellow world junior Taylor Raddysh on June 26, 2018, regarding Dub├® in the hotel room: “Man, when I was leaving, Duber was smacking this girlŌĆÖs ass so hard. Like, it looked like it hurt so bad.ŌĆØ╠²

E.M. had testified about ŌĆ£multiple peopleŌĆØ taking turns slapping her ŌĆ£as hard as they couldŌĆØ╠²and that it hurt, but was unable to identify anyone. Howden’s text would have been the piece of evidence most closely aligned to what the complainant had told the court about the slapping.╠²

Steenbergen had also testified about seeing Dub├®╠²slap the complainant on the buttocks, but agreed with a suggestion from the defence that it appeared playful and part of foreplay.╠²

Howden testified he didn’t remember sending Raddysh the text, which led the Crown to try to get it admitted through two different legal routes over several days of arguments. But both attempts failed.╠²

“The information contained in this text message is important to the Crown’s case,” Cunningham argued. ŌĆ£The text message provides what I submit is very critical corroboration for the complainantŌĆÖs testimony about one of the actual offences that is charged before the court.”

A composite image of London police Det. Steve NewtonŌĆÖs handwritten notes on the complainantŌĆÖs comments during a June 26, 2018, photo-identification interview. Michael McLeod, Dillon Dub├®, Carter Hart, Cal Foote and Alex Formenton are pictured.

Ontario Superior Court ExhibitCarroccia excluded the text╠²message from the trial; among other reasons, the fact Howden didn’t even remember sending it meant cross-examination by the defence would have been impossible, the judge found.╠²

Coristine said he imagines Cunningham would have been “alive to the possibility” that Howden would have memory problems; in trying to get the text admitted,╠²the Crown was likely keeping in mind the need to show they did everything they could, should they choose to appeal.╠²

“The Crown has to look to the future beyond the trial, even if they donŌĆÖt know what the result will be,” Coristine said.

Ultimately, Carroccia did find that╠²Dub├® slapped E.M. at some point in the night, but was not one of the multiple men E.M. referred to, and the judge said it would be wrong to separate this one instance from the “broader consensual conduct” she had already found.╠²

‘Treasure trove of evidence’ from Hockey Canada’s investigation gets thrown out╠²

As the Star reported in May, a different judge excluded during pre-trial hearings last year statements that McLeod, Formenton, and Dub├® gave to prominent ╬┌č╗┤½├Į lawyer Danielle Robitaille in 2022 as part of Hockey Canada’s independent investigation into what happened at the Delta Armouries. The players had been declining to speak to the police’s reopened probe to maintain their right to silence, but were being compelled to speak to Robitaille under penalty of a lifetime ban from Hockey Canada╠²activities and programs, which would have meant not being able to play in the Olympics, or even coach a hockey team.╠²

What Robitaille didn’t tell the players was that by August 2022, London police had told her of their intention to get a warrant for her investigative file. She pressed ahead with her interviews of the players, keeping them in the dark about the police’s plans while she grilled them about the events in the hotel room. Once the warrant was served on Robitaille’s firm in the fall of 2022, the statements were turned over to the police, and Robitaille cancelled her upcoming interviews with Hart and Foote.╠²

Humphrey, McLeod’s lawyer, described Robitaille’s investigative file as a “virtual treasure trove of evidence” when he questioned her during pre-trial hearings last year. Was she ŌĆ£oblivious,ŌĆØ Humphrey asked her, to how potentially valuable these statements could be in the hands of the police and the Crown, as they made their case for criminal charges?╠²

A photo of room 209 at the Delta Armouries hotel in London, marked up by Carter Hart during his testimony, depicting player Cal Foote doing the splits over the complainant on a bedsheet on the floor on June 19, 2018.╠²

Ontario Superior Court ExhibitŌĆ£I just didnŌĆÖt care,ŌĆØ Robitaille testified. ŌĆ£It was collateral to me.ŌĆØ

London police were hopeful in 2022 that they could gather new information from Robitaille’s work compared to what the force learned during its own investigation in 2018. In his application for a warrant, Younan said it would be reasonable to believe that Robitaille ŌĆ£asked different questions of the players than our own investigators, and therefore, elicited different answers or new information about what occurred.ŌĆØ╠²

Superior Court Justice Bruce Thomas excluded the statements because they had been obtained in an “unfair and prejudicial” way,╠²agreeing with the defence lawyersŌĆÖ descriptions of the interviews as compelled, coerced, and involuntary.

ŌĆ£I would suggest that the manner in which the applicantsŌĆÖ statements were compelled by Hockey Canada would be seen as unfair by the public and would detrimentally affect the concept of a fair trial,” he ruled.╠²

The three players told Robitaille key pieces╠²of information they had not told police during their first investigation in 2018, but it’s unclear how big a role the statements played in the police’s decision to charge them following the reopening.╠²

McLeod admitted to Robitaille he had sent a text to his teammates about coming to his room for a three-way, while claiming it was E.M.ŌĆÖs idea.╠²

Dub├® admitted to slapping E.M.ŌĆÖs buttocks. He told Robitaille he had been holding a golf club in his hand and E.M. said to him: ŌĆ£Are you going to f-ŌĆī-ŌĆī- me or play golf?ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£I was offput, didnŌĆÖt want to have sex with her in front of people,ŌĆØ╠²Dub├® said, according to notes from the interview. ŌĆ£Slapped her on bum once or twice when she said that.ŌĆØ╠²

And Formenton said he witnessed Foote do the splits over E.M.ŌĆÖs face without pants.╠²ŌĆ£A guy says Foote can do the splits; she says OK,ŌĆØ Formenton recalled. ŌĆ£So sheŌĆÖs laying on the ground parallel between the beds.╠²I remember he takes pants off, top clothes still on, does splits over her upper body.ŌĆØ

The Crown had hoped to use the statements to highlight any inconsistencies between what the players said on the stand, should they choose to testify, versus what they told Robitaille. But in the end only Hart, who had never given a previous statement about the events in the hotel room,╠²testified in his own defence.╠²

‘The burden rests squarely on the Crown’

In her judgement Thursday, Carroccia said the case had a “lengthy and contorted history” involving multiple investigations by different agencies, leading to conflicting statements from E.M., the accused men and other witnesses. “With five accused and that barrage of evidence, I can say that counsel conducted the trial efficiently, and that the time spent, particularly in the cross-examination of E.M., was entirely appropriate,” she said.╠²

The judge emphasized that a person accused of a crime is innocent unless and until the Crown has proven their guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. In the face of ongoing criticism of what happened in the room╠²ŌĆö the NHL said Thursday that despite the not-guilty verdicts, the allegations were “very disturbing and the behaviour at issue was unacceptable”╠²ŌĆö Carroccia reminded the public through her ruling what the real purpose was of this eight-week trial.╠²

“It is not the function of this court to make determinations about the morality or propriety of the conduct of any of the persons involved in these events,” she said.╠²

“The sole function of this court is to determine whether the Crown has proven each of the charges against each of the accused beyond a reasonable doubt. The burden rests squarely on the Crown and does not shift.”

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation